Economic and Racial Inequality in FEMA SFHA Flood Zone Designations

● ~76% of Single-Family Residential flood risk in the US is not covered by the FEMA Special Flood Hazard Assessment (SFHA) 100-year flood zones that are also used to determine residential flood insurance requirements for government-backed home loans.

● Populations that spend the most relative income on housing are ~1.5x more likely than the least housing cost-burdened to be exposed to flood risk not covered by FEMA SFHAs. SFHAs in their current form are financially regressive with respect to flood risk and resilience.

● Even after accounting for housing cost-burden, non-white populations are significantly more likely to face flood risk that is not captured in FEMA SFHAs — at every level of flood risk. Asian, Black, Native American, and Latino populations are only ~29%, ~65%, ~70%, and ~72%, respectively, as likely as white-alone populations to have flood risk accounted for by FEMA SFHAs.

● With no evidence for correlation between race/affluence and NFIP insurance policy take-up rates, SFHA disparities result in poorer people and communities of color bearing a disproportionate burden of uninsured flood risk and, all other things held equal, a disproportionate amount of mortgage delinquency and wealth destruction.

● Climate change without any change in SFHA approach is set to enhance inequality in the US, with a ~19% increase in expected annual losses to 2050 in inland areas, which are where the greatest SFHA inequality exists.

● Risk Rating 2.0 (RR2.0), which is designed in large part to make the NFIP more equitable, only addresses premium re-pricing in existing FEMA SFHAs. We clearly show that it will still fall short of achieving that goal given historical preferential investment in generally whiter and more affluent neighborhoods.

● Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs) — Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae — which have a mandate to make home ownership possible and affordable to lower- and middle-income populations, are reliant on SFHA, creating regressive architecture in programs intended to be the opposite.

● To build a more equitable and sustainable program, FEMA should focus on restorative investment in terms of immediate action on floodplain modeling in historically disadvantaged areas, thereby making flood insurance much more accessible, in particular to these communities that have been left behind.

Bottom-up Analysis of Top-down Climate Injustice

FEMA has been in the spotlight recently given analyses showing that poorer communities and particularly people of color tend to receive less aid post-disaster, driven by a combination of external circumstance and internal policies and their collective consequences.

What follows is new analysis showing that FEMA has also failed to invest equitably pre-disaster, specifically in terms of its design of FEMA SFHA 100-year flood zones in the context of communities that are disproportionately non-white and housing cost-stressed, which again often aligns with poorer communities with smaller safety nets.

Most US Flood Risk is Uninsured

FEMA Special Flood Hazard Assessment (SFHA) 100-year flood zones are used to determine residential flood insurance requirements for government-backed home loans. While there is a scale within the SFHA labeling, it nonetheless creates a binary “in” or “out” construct from which flood insurance decisions are compulsorily or voluntarily made. Overlaying SFHA with our own national flood risk and property value maps, we estimate that ~76% of Single Family Residential (SFR) flood risk across the US is “out” of the FEMA SFHA zones. Within this astounding number, coastal communities, which have higher flood risk on average, tend to have more SFHA coverage and alignment with actual flood risk. However, that also means that even greater and systemic gaps exist in inland flood risk, along with the visibility the general population has to act upon it.

Critically, homes purchased in areas outside SFHAs are not required to purchase NFIP insurance by mortgage originators. In these areas, voluntary take-up rates are at most around ~3% nationally (though this varies significantly by location). The take-up rates obviously jump in SFHA areas, but not as much as might be expected. A 2018 analysis by Wharton’s Risk Management and Decision Process Center estimated that the NFIP insurance take-up rate in SFHAs is only ~30%. (According to that same report, a smaller percentage of residential flood risk is carried by private insurers; this analysis does not cover private flood insurance.) Our analysis based on 2019 NFIP policy data suggests this take-up is similar, but closer to ~25%. Putting all of these numbers together suggests that less than 10% of the nation’s total single family residential flood risk is actually insured by the NFIP. That is a toxin sitting in the residential real estate market that will only worsen with climate change. Perhaps even more concerning to the US taxpayer, many loans in the areas with greatest amounts of uninsured flood risk are passed on to one of the Government Sponsored Enterprises — Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac — as part of their core mission to enable home ownership(more on that later). For now, keep in mind that there is a 10x increase in flood insurance take-up rates when “in” vs “out” of SFHA.

Economic Affluence and FEMA 100-Year Flood Zones

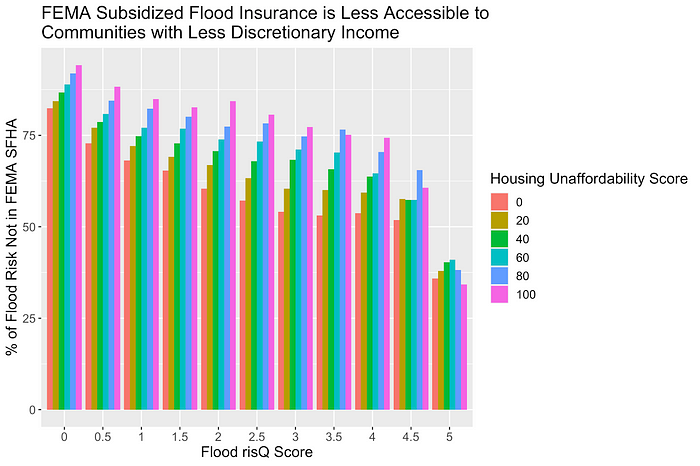

risQ’s Housing Unaffordability Score is a 0–100 composite index that measures income relative to housing costs, leveraging multiple root variables from the American Community Survey (ACS), where higher scores translate to lower levels of discretionary income, i.e., smaller safety nets. The Flood risQ Score is a relative score ranging 0–5 that ranks communities (defined here as census tracts) in terms of their total flood risk measured across inland (fluvial and pluvial) flood and non-hurricane coastal flood. Each 1.0-point increase implies an approximate doubling of financial risk from flood.

In Figure 1, we round and cross-tabulate these 2 scores into 66 bins and then analyze the percentage of residential exposure-weighted total flood risk that falls within FEMA SFHAs for each bin. The results show two clear and systematic patterns: first, as total flood risk increases, so does the percentage that is designated within an SFHA. This is to be expected given that, very broadly, FEMA has at least prioritized regions of the country with higher flood risk. Second, and more alarmingly, as housing cost relative to the income of a community increases, SFHA coverage decreases significantly and consistently across different levels of flood risk.

Using a regression model that controls for population density, total flood risk as defined by the Flood risQ Score, and broad state-level differences, we estimate that populations that spend the most relative income on housing are ~1.5x more likely than the least housing cost-burdened to have flood risk not accounted for by FEMA SFHAs. Expressed differently, communities with the least affordable housing and least discretionary income are systemically predisposed to being less insured.

Racial Composition and FEMA 100-Year Flood Zones

Affluence and housing affordability are just one lens through which climate justice can be viewed. In addition, the less white a community is, the less access it has to FEMA’s NFIP flood insurance, on average. Figure 2 below shows this broken out again by Flood risQ Score, but this time against the percentage of the population identifying as white. The figure makes it clear that no matter the level of flood risk, communities with a smaller white population share are significantly more likely to be exposed to flood risk that is not captured as SFHA; this is particularly true for the most extreme flood risk cohorts (Flood risQ Score >= 4.5).

Note that Figure 2 does not yet account for affluence as defined in Figure 1. Race and affluence remain highly correlated: over all census tracts, the Spearman rank correlation between the Housing Unaffordability Score and the percentage of non-white population is 0.63. In other words, non-white populations tend to spend a larger proportion of income on housing and thus have a smaller safety net. All that said, we have isolated race as a correlating factor to SFHA coverage.

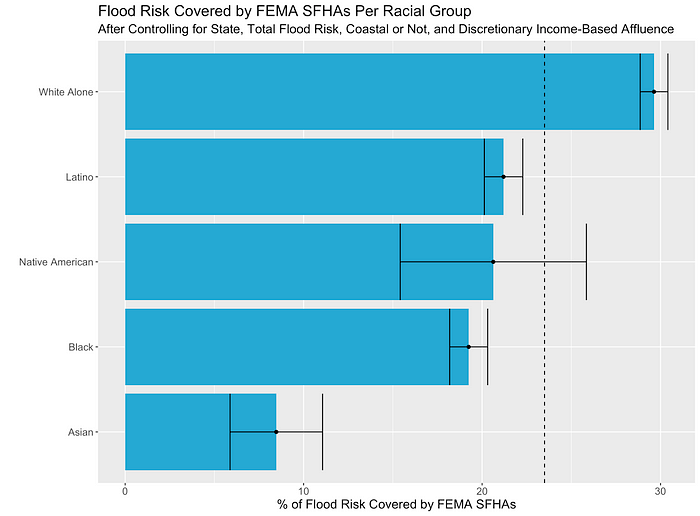

Next, after the regression model discussed earlier is used to control for relative affluence via the Housing Unaffordability Score, population density, total flood risk (via the Flood risQ Score), variance among states, and whether a tract is directly on the coast — a series of simple linear regression models are then used to isolate the differentials in flood risk SFHA coverage by racial category.

Figure 3 shows the results of those regression models. On average, we estimate that Asian, Black, Native American, and Latino populations are only ~29%, ~65%, ~70%, and ~72%, respectively, as likely as white-alone populations to have their flood risk accounted for by FEMA SFHAs.

Using residuals from the regression model, i.e., after controlling for variables described earlier, tracts are classified as either having more or less than expected flood risk accounted for by an SFHA. For high flood risk tracts (Flood risQ Score >= 3), Table 1 tabulates these for tracts with >= 80% white-alone, >=25% Asian, Black, and Latino, and >= 10% Native American populations, broken down by whether a tract is directly on the coast. Much of the aforementioned race disparity in these high flood risk areas comes from non-coastal census tracts. The blanket SFHA treatment for coastal areas brings more communities along for the ride — “a rising tide floats all boats,” as it were — but there is no rationale for the marked differences once the oceanfront views disappear.

Results are similar no matter the flood risk threshold. Figure 4 illustrates this phenomenon spatially for >=25% Black versus >=80% white-only tracts in Louisiana, showing only those with high flood risk (Flood risQ Score >= 3). Across New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Alexandria, tracts with high flood risk that have less SFHA coverage than expected (red areas) are disproportionately those with larger shares of Black population (orange outline).

Figure 5 illustrates this same phenomenon spatially for >=25% Asian versus white-only tracts in California, again showing only tracts with high flood risk (Flood risQ Score >= 3). In the greater San Francisco area, tracts with high flood risk that have less SFHA coverage than expected (red areas) are disproportionately those with larger shares of Asian population (orange outline). Note the very different patterns of tracts in substantially white Marin County to the north compared to those in San Mateo and Alameda counties to the south and east of San Francisco. Both of the latter have combined Asian and Latino populations of >50%, indicating a greater regionality at the county level, which is also where much of the engagement with FEMA occurs.

This can be broadened out to look at coastal versus inland tracts on a state-by-state basis. Figure 6 shows a state-level summary of the percentage of tracts by state that have less than expected flood risk (regardless of level of risk) accounted for by SFHAs, for tracts with >=80% white-only population versus those with <80% white only population. Similar to Table 1, for inland tracts, the vast majority of states (41/49) exhibit preferential SFHA flood risk coverage for predominantly white communities. The pattern is not as clear for coastal tracts, where 11/20 show that same preference. Generally, although with exceptions, states that are not in the southeastern United States show a stronger SFHA coverage preference for whiter communities.

And Let’s Not Forget, There’s Climate Change

A recent study showed that current cumulative carbon dioxide emissions, which is what determines global-mean temperature, fall within 1% of those predicted by RCP8.5, the most extreme of the Representative Concentration Pathways developed by the IPCC. It is important to keep in mind that the RCP8.5 2020 cumulative carbon dioxide value comes from 15 years of projected emission concentrations (2005–2020). As the authors emphasize, the 2020 cumulative carbon dioxide value is so close in agreement with the RCP8.5 projection that the 15 years of mitigation and emission reduction required under RCP4.5 clearly did not occur. By corollary, this means we’re already halfway to RCP8.5 being our 2050 reality.

How bad is that for the US given the extent of uninsured risk we know exists? Let’s focus on inland flood, a phenomenon that is paid too little attention in general and by FEMA based on the collective analysis above. The 2050 RCP8.5 scenario for inland flood risk sees the total loss cost for single family residential homes increase by ~19% — bringing the annual expected loss cost up from ~$48B to ~$56B. The greater New England area down through the Midwest carries much of that burden. The vast majority of that risk won’t have flood insurance going on current insurance take-up rate trends. Unless things change, that risk will enhance existing levels of inequality. Needless to say, the southeast (for hurricane risk) and coastal areas (for coastal flooding) will have their own RCP8.5 cross to bear.

Risk Rating 2.0 Implications and What FEMA Should Do

Most people do not purchase flood insurance if they do not have to, these same disproportionately non-white and financially-pinched populations are virtually certain to be less insured, consequently left absorbing more flood risk.

Risk Rating 2.0, which seeks to make flood insurance more equitable by basing it on actual flood risk rather than subsidizing affluence (as it has historically), is one big step in the right direction. But its aim is not to redefine what its SFHA zones actually are, and as such it will still leave disproportionately non-white and income-stressed communities further behind. Steps should be taken and investment should be made to close this insurance zone gap. To build a more equitable and sustainable program, FEMA should also focus on restorative investment, in terms of immediate action on floodplain modeling in historically disadvantaged areas, thereby making flood insurance much more accessible, in particular to these communities that have been left behind.

Numerous opportunities also exist to leverage a wider community to efficiently update SFHA areas and the Flood Insurance Rate Maps. Numerous data sources exist to model flood risk on a national basis that could be leveraged while more extensive area-by-area analyses are conducted in higher risk and/or historically disadvantaged areas. Using a high confidence set of flood data from different parts of the country, a simple hold-out test of which data set or combination thereof matches FEMA’s data could be completed and then used as a best-in-class, low-cost, broad-coverage basis for SFHA determination. This would also create the potential for a nationally levelized, 100% transparent grey-scale approach to flood risk and differing levels of flood insurance coverage and cost. This also means that disadvantaged communities won’t have to wait in line while more affluent white communities protest and appeal new flood maps designed for their own benefit, even if they don’t realize it. While such communities suck up limited resources by protesting edge cases and methodology, less affluent communities would gladly take and benefit from their new SFHA information.

In the meantime, the agency should clearly communicate the value of having NFIP (or other flood) insurance inside and outside SFHAs. FEMA should also explore ways to streamline the purchase of flood insurance in general.

What The US Housing Market Can Do

The Government Sponsored Entities (GSEs) — Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae — have a mandate to make home ownership possible and affordable to lower- and middle-income populations. Since GSEs currently only know the flood risk that sits on their books in terms of whether a loan sits in an SFHA, and given that most flood risk does not reside in SFHAs, they are operating in the dark in terms of how much flood risk they actually hold. Leveraging the geospatial linking capability of our partner Level11 Analytics, we analyzed ~$7.2T of Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, and Ginnie Mae total current outstanding home loan value and found that ~74–77% of the flood risk those loans are exposed to falls outside of SFHAs.

This is all vital with respect to wealth creation, where home ownership has historically been foundational. Much of the above data has highlighted areas where the Flood risQ Score is >=3. We have previously shown that once risQ Scores exceed 3, there is a statistically significant escalation in mortgage payment delinquency. Given a 10x difference flood insurance uptake in SFHA vs non-SFHA, and poorer and/or non-white communities having disproportionately higher amounts of their high flood risk outside of SFHA, concentration of mortgage delinquency in those same communities will follow. The SFHA process in its current form creates outsized risk of wealth destruction in exactly the communities that GSE’s might help the most.

The GSE’s should consider requiring modest but affordable NFIP or private flood insurance coverage for conforming home loans in areas with flood risk outside of FEMA’s SFHA zones — potentially in FEMA’s 500-year flood zones, or even in flood zones defined by one or more risk models developed by organizations beyond FEMA. This could serve all stakeholders: low- and middle-income homeowners that live in risky areas that are not captured by SFHAs would be covered in flood events, which are becoming more intense and frequent in nature. Requiring a significantly larger proportion (or all) homebuyers to purchase flood insurance at some level (even nominal) corresponding to a more continuous versus binary flood risk metric would likely have the effect of making the NFIP more fiscally stable as well. Finally, the GSEs current lack of crucial information would be mitigated, allowing for better construction and disclosure of Credit Risk Transfer (CRT) bonds that are sold to investors, ultimately a form of taxpayer insurance.

Conclusion

Intentionally or otherwise, the current system for SFHA determination and its role in driving flood insurance uptake has resulted in substantial liabilities and risk in US residential real estate at the individual and collective level. This risk systemically and disproportionately impacts less affluent and minority communities. Without an alternate approach, the scale of the risk and the scale of the disparity will only get worse with climate change. Unless things change, climate injustice will be as much an intra-US outcome as it is a global sovereign outcome, with government agencies being part of the problem, not part of the solution.